Peace Without Parity? The Hidden Cost for Women in Post-War Deals

When conflicts end, the world often celebrates the signing of peace agreements, envisioning a fresh start. But beneath the headlines, a critical question often goes unasked: Is this peace truly equitable? For countless women in post-war nations, the answer is often a resounding no.

- Ornella Jameson

- Jul 04, 2025

- 0 Comments

- 2423 Views

This article delves into the hidden cost of peace deals that overlook gender parity, exploring how excluding women from recovery and reconstruction efforts perpetuates inequalities and undermines the very stability these agreements aim to achieve.

1. The Gender Gap in Post-War Peace Processes

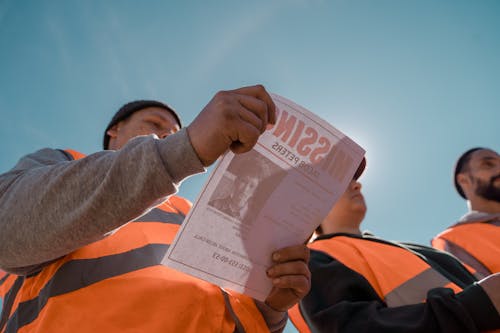

When conflicts end and peace agreements are signed, the world often celebrates—but women’s voices remain largely absent from the negotiating table. Despite international advocacy, women made up only 13% of negotiators and 6% of mediators in major peace processes from 1992 to 2019, and these numbers remain stubbornly low. Peace talks are typically dominated by political and military elites—overwhelmingly men—leaving women’s perspectives and priorities sidelined.

This exclusion is not just a matter of numbers. When women are absent, peace agreements often fail to address the specific needs and rights of women and girls. Gender-blind deals can perpetuate discrimination, insecurity, and economic marginalization, with post-war societies frequently ignoring the unique challenges faced by women, such as increased domestic violence and barriers to economic participation.

2. The Cost of Exclusion

The exclusion of women from peacebuilding is not only unjust. it is counterproductive. Research from the Council on Foreign Relations (2021) finds that peace agreements are 35% more likely to last at least 15 years when women are involved. Women's participation brings unique perspectives on community needs, transitional justice, and social healing. When excluded, peace deals often fail to address gender-based violence, land rights, and education:issues that disproportionately affect women post-conflict.

- Liberia's civil war (1989–2003) showcased both the power of women's movements and the limits of institutional recognition. The Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace, led by Leymah Gbowee, helped force warring factions to negotiate. Their activism was instrumental in ending the conflict, yet women were minimally represented in the formal peace talks. Post-war policies improved slightly with Ellen Johnson Sirleaf's presidency, but structural inequities persisted in recovery programs, particularly in land reform and justice systems.

- The 2016 peace deal between the Colombian government and FARC was initially celebrated for its gender-sensitive provisions, thanks to the tireless efforts of feminist organizations. Colombia's Gender Sub-Commission was a groundbreaking model. However, implementation has faltered. A 2022 Kroc Institute report found that only 22% of the gender-related commitments had been fully implemented six years later. Rural women, particularly Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities, continue to face barriers in accessing promised resources and protections.

- In Syria, protracted conflict and fragmented peace efforts have largely marginalized women. UN-led peace talks have included few Syrian women, despite civil society networks like the Syrian Women's Advisory Board. As of 2021, women comprised less than 15% of participants in official negotiations. Moreover, donor funding for gender-focused reconstruction programs remains critically low, despite widespread sexual violence and displacement impacting women disproportionately (Human Rights Watch, 2021).

- Several structural and sociopolitical barriers contribute to women's exclusion. These include patriarchal norms, lack of political will, security risks, and limited access to education and networks. Post-war environments often revert to "traditional" roles, sidelining women under the guise of stability. Additionally, peace processes are typically elite-driven, favoring political and military actors over grassroots voices.

- Achieving inclusive peace requires both structural reform and cultural change. Quota systems for female representation, funding for women's organizations, and gender mainstreaming in DDR (Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration) and SSR (Security Sector Reform) programs are essential. The UNSCR 1325 framework on Women, Peace, and Security remains a critical tool, yet enforcement remains inconsistent across regions.

3. Towards Inclusive and Sustainable Peace

Building a lasting peace requires the meaningful participation of women at every stage of the process. Evidence shows that gender-sensitive agreements are more likely when women are involved in negotiations, civil society, and national parliaments. Strong networks of women peacebuilders and intergenerational leadership are crucial for advancing gender equality in post-conflict societies.

To achieve true parity, peace processes must mandate women’s representation, include clear and actionable gender provisions, and provide sustained support for women’s organizations. Peacebuilding initiatives should be designed to address the everyday security concerns of women, ensuring that the risks they face are recognized and mitigated. Only by embracing the full and equal participation of women can post-war societies build a peace that is not only lasting but truly just for all.

References

- UN Women (2020). Women’s Participation in Peace Processes. Retrieved from https://www.unwomen.org

- Council on Foreign Relations (2021). Women’s Participation in Peace Processes. Retrieved from https://www.cfr.org

- Human Rights Watch (2021). Syria: Events of 2020. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org

- Kroc Institute (2022). Sixth Report on the Implementation of the Colombian Final Accord. University of Notre Dame.

- Gbowee, L. (2011). Mighty Be Our Powers: How Sisterhood, Prayer, and Sex Changed a Nation at War. Beast Books.

| Unlock Success with Our Guide

| Unlock Success with Our Guide

0 Comments